The dot-com bubble (also known as the dot-com boom, the tech bubble, the Internet bubble, the dot-com collapse, and the information technology bubble was a historic speculative bubble covering roughly 1995–2001 during which stock markets in industrialized nations saw their equity value rise rapidly from growth in the Internet sector and related fields. While the latter part was a boom and bust cycle, the Internet boom is sometimes meant to refer to the steady commercial growth of the Internet with the advent of the World Wide Web, as exemplified by the first release of the Mosaic web browser in 1993, and continuing through the 1990s.

The period was marked by the founding (and, in many cases, spectacular failure) of several new Internet-based companies commonly referred to as dot-coms. Companies could cause their stock prices to increase by simply adding an “e-” prefix to their name or a “.com” suffix, which one author called “prefix investing.” A combination of rapidly increasing stock prices, market confidence that the companies would turn future profits, individual speculation in stocks, and widely available venture capital created an environment in which many investors were willing to overlook traditional metrics, such as P/E ratio, in favor of basing confidence on technological advancements. By the end of the 1990s, the NASDAQ hit a price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of 200, a truly astonishing plateau that dwarfed Japan’s peak P/E ratio of 80 a decade earlier.

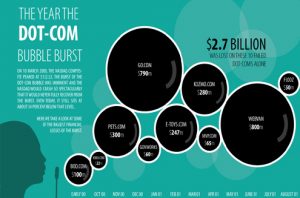

The collapse of the bubble took place during 1999–2001. Some companies, such as pets.com and Webvan, failed completely. Others – such as Cisco, whose stock declined by 86% – lost a large portion of their market capitalization but remained stable and profitable. Some, such as eBay.com, later recovered and even surpassed their dot-com-bubble peaks. The stock of Amazon.com came to exceed $700 per share, for example, after having gone from $107 to $7 in the crash.

Bubble growth

Due to the rise in the commercial growth of the Internet, venture capitalists saw record-setting growth as “dot-com” companies experienced meteoric rises in their stock prices and therefore moved faster and with less caution than usual, choosing to mitigate the risk by investing in many contenders and letting the market decide which would succeed. The low interest rates of 1998–99 helped increase the start-up capital amounts. A canonical “dot-com” company’s business model relied on harnessing network effects by operating at a sustained net loss and building market share (or mind share). These companies offered their services or end product for free with the expectation that they could build enough brand awareness to charge profitable rates for their services later. The motto “get big fast” reflected this strategy.

This occurred in industrialized nations due to the reducing “digital divide” in the late 1990s, and early 2000s. Previously, individuals were less capable of accessing the Internet, many stopped by lack of local access/connectivity to the infrastructure, and/or the failure to understand use for Internet technologies. The absence of infrastructure and a lack of understanding were two major obstacles that previously obstructed mass connectivity. For these reasons, individuals had limited capabilities in what they could do and what they could achieve in accessing technology. Increased means of connectivity to the Internet than previously available allowed the use of ICT (information and communications technology) to progress from a luxury good to a necessity good. As connectivity grew, so did the potential for venture capitalists to take advantage of the growing field. The functionalism, or impacts of technologies driven from the cost effectiveness of new Internet websites ultimately influenced the demand growth during this time.

Soaring stocks

In financial markets, a stock market bubble is a self-perpetuating rise or boom in the share prices of stocks of a particular industry; the term may be used with certainty only in retrospect after share prices have crashed. A bubble occurs when speculators note the fast increase in value and decide to buy in anticipation of further rises, rather than because the shares are undervalued. Typically, during a bubble, many companies thus become grossly overvalued. When the bubble “bursts”, the share prices fall dramatically. The prices of many non-technology stocks increased in tandem and were also pushed up to valuations discorrelated relative to fundamentals.

American news media, including respected business publications such as Forbes and the Wall Street Journal, encouraged the public to invest in risky companies, despite many of the companies’ disregard for basic financial and even legal principles.

Andrew Smith argued that the financial industry’s handling of initial public offerings tended to benefit the banks and initial investors rather than the companies. This is because company staff were typically barred from reselling their shares for a lock-in period of 12 to 18 months, and so did not benefit from the common pattern of a huge short-lived share price spike on the day of the launch. In contrast, the financiers and other initial investors were typically entitled to sell at the peak price, and so could immediately profit from short-term price rises. Smith argues that the high profitability of the IPOs to Wall Street was a significant factor in the course of events of the bubble. He writes:

“But did the kids [the often young dotcom entrepreneurs] dupe the establishment by drawing them into fake companies, or did the establishment dupe the kids by introducing them to Mammon and charging a commission on it?”

In spite of this, however, a few company founders made vast fortunes when their companies were bought out at an early stage in the dot-com stock market bubble. These early successes made the bubble even more buoyant. An unprecedented amount of personal investing occurred during the boom, and the press reported the phenomenon of people quitting their jobs to become full-time day traders.

Academics Preston Teeter and Jorgen Sandberg have criticized Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan for his role in the promotion and rise in tech stocks. Their research cites numerous examples of Greenspan putting a positive spin on historic stock valuations despite a wealth of evidence suggesting that stocks were overvalued.

Free spending

According to dot-com theory, an Internet company’s survival depended on expanding its customer base as rapidly as possible, even if it produced large annual losses. For instance, Google and Amazon.com did not see any profit in their first years. Amazon was spending to alert people to its existence and expand its customer base, and Google was busy spending to create more powerful machine capacity to serve its expanding web search engine. The phrase “Get large or get lost” was the wisdom of the day. At the height of the boom, it was possible for a promising dot-com to make an initial public offering (IPO) of its stock and raise a substantial amount of money even though it had never made a profit—or, in some cases, earned any revenue whatsoever. In such a situation, a company’s lifespan was measured by its burn rate: that is, the rate at which a non-profitable company lacking a viable business model ran through its capital.

Public awareness campaigns were one of the ways in which dot-coms sought to expand their customer bases. These included television ads, print ads, and targeting of professional sporting events. Many dot-coms named themselves with onomatopoeic nonsense words that they hoped would be memorable and not easily confused with a competitor. Super Bowl XXXIV in January 2000 featured 16 dot-com companies that each paid over $2 million for a 30-second spot. By contrast, in January 2001, just three dot-coms bought advertising spots during Super Bowl XXXV. In a similar vein, CBS-backed iWon.com gave away $10 million to a lucky contestant on an April 15, 2000 half-hour primetime special that was broadcast on CBS.

Not surprisingly, the “growth over profits” mentality and the aura of “new economy” invincibility led some companies to engage in lavish internal spending, such as elaborate business facilities and luxury vacations for employees. Executives and employees who were paid with stock options instead of cash became instant millionaires when the company made its initial public offering; many invested their new wealth into yet more dot-coms.

Cities all over the United States sought to become the “next Silicon Valley” by building network-enabled office space to attract Internet entrepreneurs. Communication providers, convinced that the future economy would require ubiquitous broadband access, went deeply into debt to improve their networks with high-speed equipment and fiber optic cables. Companies that produced network equipment like Nortel Networks were irrevocably damaged by such over-extension; Nortel declared bankruptcy in early 2009. Companies like Cisco, which did not have any production facilities, but bought from other manufacturers, were able to leave quickly and actually do well from the situation as the bubble burst and products were sold cheaply.

In the struggle to become a technology hub, many cities and states used tax money to fund technology conference centers, advanced infrastructure, and created favorable business and tax law to encourage development of the dotcom industry in their locale. Virginia’s Dulles Technology Corridor is a prime example of this activity. Large quantities of high-speed fiber links were laid, and the State and local governments gave tax exemptions to technology firms. Many of these buildings could be viewed along I-495, after the burst, as vacant office buildings.

Similarly, in Europe the vast amounts of cash the mobile operators spent on 3G licences in Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom, for example, led them into deep debt. The investments were far out of proportion to both their current and projected cash flow, but this was not publicly acknowledged until as late as 2001 and 2002. Due to the highly networked nature of the IT industry, this quickly led to problems for small companies dependent on contracts from operators. One example is of a then Finnish mobile network company Sonera, which paid huge sums in German broadband auction then dubbed as 3G licenses. Third-generation networks however took years to catch on and Sonera ended up as a part of TeliaSonera, then simply Telia.

Aftermath

On January 10, 2000, America Online (now Aol.), a favorite of dot-com investors and pioneer of dial-up Internet access, announced plans to merge with Time Warner, the world’s largest media company, in the second-largest M&A transaction worldwide. The transaction has been described as “the worst in history”. Within two years, boardroom disagreements drove out both of the CEOs who made the deal, and in October 2003 AOL Time Warner dropped “AOL” from its name.

On March 10, 2000 the NASDAQ peaked at 5,132.52 intraday before closing at 5,048.62. Afterwards, the NASDAQ fell as much as 78%.

Several communication companies could not weather the financial burden and were forced to file for bankruptcy. One of the more significant players, WorldCom, was found engaging in illegal accounting practices to exaggerate its profits on a yearly basis. WorldCom was one of the last standing combined competitive local exchange and inter-exchange companies and struggled to survive after the implementation of the Telecommunications Act of 1996. This Act favored incumbent players formerly known as Regional Bell Operating Companies (RBOCS) and led to the demise of competition and the rise of consolidation and a current day oligopoly ruled by lobbyist saturated powerhouses AT&T and Verizon.

WorldCom’s stock price fell drastically when this information went public, and it eventually filed the third-largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history. Other examples include NorthPoint Communications, Global Crossing, JDS Uniphase, XO Communications, and Covad Communications. Companies such as Nortel, Cisco, and Corning were at a disadvantage because they relied on infrastructure that was never developed which caused the stock of Corning to drop significantly.

Many dot-coms ran out of capital and were acquired or liquidated; the domain names were picked up by old-economy competitors, speculators or cybersquatters. Several companies and their executives were accused or convicted of fraud for misusing shareholders’ money, and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission fined top investment firms like Citigroup and Merrill Lynch millions of dollars for misleading investors. Various supporting industries, such as advertising and shipping, scaled back their operations as demand for their services fell. A few large dot-com companies, such as Amazon.com, eBay, and Google have become industry-dominating mega-firms.

The stock market crash of 2000–2002 caused the loss of $5 trillion in the market value of companies from March 2000 to October 2002. The September 11, 2001, attacks accelerated the stock market drop; the NYSE suspended trading for four sessions. When trading resumed, some of it was transacted in temporary new locations.

More in-depth analysis shows that 48% of the dot-com companies survived through 2004. With this, it is safe to assume that the assets lost from the stock market do not directly link to the closing of firms. More importantly, however, it can be concluded that even companies who were categorized as the “small players” were adequate enough to endure the destruction of the financial market during 2000–2002. Additionally, retail investors who felt burned by the burst transitioned their investment portfolios to more cautious positions.

Nevertheless, laid-off technology experts, such as computer programmers, found a glutted job market. University degree programs for computer-related careers saw a noticeable drop in new students. Anecdotes of unemployed programmers going back to school to become accountants or lawyers were common.

Turning to the long-term legacy of the bubble, Fred Wilson, who was a venture capitalist during it, said:

“A friend of mine has a great line. He says ‘Nothing important has ever been built without irrational exuberance’. Meaning that you need some of this mania to cause investors to open up their pocketbooks and finance the building of the railroads or the automobile or aerospace industry or whatever. And in this case, much of the capital invested was lost, but also much of it was invested in a very high throughput backbone for the Internet, and lots of software that works, and databases and server structure. All that stuff has allowed what we have today, which has changed all our lives… that’s what all this speculative mania built”.

As the technology boom receded, consolidation and growth by market leaders caused the tech industry to come to more closely resemble other traditional U.S. sectors. As of 2014, ten information technology firms are among the 100 largest U.S. corporations by revenues: Apple, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Microsoft, Amazon.com, Google, Intel, Cisco Systems, Ingram Micro, and Oracle.

Conclusion

The Dot-com Bubble of the 1990s and early 2000s was characterized by a new technology which created a new market with many potential products and services, and highly opportunistic investors and entrepreneurs who were blinded by early successes. After the crash, both companies and the markets have become a lot more cautious when it comes to investing in new technology ventures. It might be noted, though, that the current popularity of mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets, and their almost infinite possibilities, and the fact that there have been a few successful tech IPOs recently, will give life to a whole new generation of companies that want to capitalize on this new market. Let’s see if investors and entrepreneurs are a bit more sensible this time around.