Bell Atlantic Corporation was created as one of the original Regional Bell Operating Companies (RBOCs) in 1984, during the breakup of the Bell System. Bell Atlantic originally operated in the states of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, and Virginia, as well as Washington, DC. In 1994, Bell Atlantic became the first RBOC to entirely drop the original names of its original operating companies. In 1996, CEO and Chairman Raymond W. Smith orchestrated Bell Atlantic’s merger with NYNEX. When it merged, it moved its corporate headquarters from Philadelphia to New York City. NYNEX was consolidated into this name by 1997.

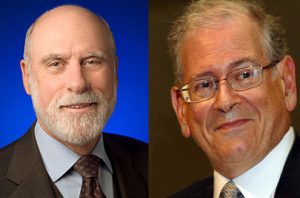

Verizon Communications formed in June 2000 when the Federal Communications Commission approved a US$64.7 billion merger of telephone companies Bell Atlantic and GTE, nearly two years after the deal was proposed in July 1998. The approval came with 25 stipulations to preserve competition between local phone carriers, including investing in new markets and broadband technologies. The new venture was headed by co-CEOs Charles Lee, formerly the CEO of GTE, and Bell Atlantic CEO Ivan Seidenberg. What eventually became Verizon was founded as Bell Atlantic, which was one of the seven Baby Bells that were formed after AT&T Corporation was forced to relinquish its control of the Bell System by order of the Justice Department of the United States. Bell Atlantic came into existence in 1984 with a footprint from New Jersey to Virginia, with each area having a separate operating company (consisting of New Jersey Bell, Bell of Pennsylvania, Diamond State Telephone, and C&P Telephone). As part of the rebranding that the Baby Bells took in the mid-1990s, all of the operating companies assumed the Bell Atlantic name. In 1997, Bell Atlantic expanded into New York and the New England states by merging with fellow Baby Bell NYNEX. In addition, Bell Atlantic moved their headquarters from Philadelphia into the old NYNEX headquarters and rebranded the entire company as Bell Atlantic.

In 2000, Bell Atlantic merged with GTE, which operated telecommunications companies across most of the rest of the country that was not already in Bell Atlantic’s footprint. Bell Atlantic, the surviving company, changed its name to “Verizon”, a portmanteau of veritas (Latin for “truth”) and horizon. As of 2016, Verizon is one of three companies that had their roots in the former Baby Bells. The other two, like Verizon, exist as a result of mergers among fellow former Baby Bell members. One, SBC Communications, bought out its former parent AT&T Corporation and assumed the AT&T name. The other, CenturyLink, was formed initially in 2011 by the acquisition of Qwest (formerly named US West).

Company History:

Bell Atlantic Corporation is growing ever-more prominent in U.S. and international telecommunications with assets of almost $54 billion. The company’s 1997 merger with NYNEX made it the second largest telephone company in the United States with nearly 40 million telephone access lines, 5.4 million wireless customers, and 4.4 million miles of fiber optic cabling. Additionally, Bell Atlantic is the world’s largest publisher of Yellow Pages directories, with over 80 million copies distributed annually, while its global telecommunications services include investments and state-of-the-art ventures in 21 countries.

The Breakup of AT&T: 1982-84

In January 1982 the U.S. Department of Justice ended a 13-year antitrust suit against the world’s largest corporation, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T). Pursuant to a consent decree, AT&T maintained its manufacturing and research facilities, as well as its long-distance operations. On January 1, 1984, AT&T divested itself of 22 local operating companies, which were divided among seven regional holding companies (RHCs).

Thus Bell Atlantic was free of AT&T; the company served the northern Atlantic states and oversaw seven telephone subsidiaries. AT&T as a tough competitor rather than a parent company proved an immediate and ever-present challenge for Bell Atlantic. On January 2, 1984, Federal Justice Harold Greene ordered Bell Atlantic to transfer a $30 million contract with the federal government to AT&T, ruling that AT&T was granted the contract pre-divestiture. Bell Atlantic claimed that many terms of the contract–which included the sale of 200,000 telephones, a year-long maintenance contract worth $6 million involving approximately 275 employees–were made directly with Bell Atlantic, not AT&T. Bell Atlantic argued, also unsuccessfully, that the transfer of employees would give AT&T knowledge of Bell Atlantic’s advanced voice and data communications Centrex system, so that AT&T could conceivably design and market a system to underprice Bell Atlantic.

Nevertheless, Bell Atlantic bounced back from its court loss, acquiring a 40 percent interest in A Beeper Company Associates in January 1984. The following month the company announced the formation of Bell Atlanticom Systems, a systems and equipment subsidiary, to market traditional, cordless, and decorator telephones, wiring components, and home security and healthcare systems. Bell Atlantic Mobile Systems took off early from the starting gate: in March 1984 the company introduced Alex, a cellular telephone service to commence a month later in the Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland, markets. Bell Atlantic Mobile Systems invested $15.1 million in the fledgling cellular service.

During this time, skirmishes continued between the RHCs, AT&T, and Justice Harold Greene. Greene asserted that the RHCs were more concerned with entering new business markets than in improving the local networks. In an effort to restrain RHCs from using regulated business profits to finance non-telephone ventures, the consent decree ruled that new endeavors may comprise no more than ten percent of the RHCs’ yearly revenues and that there be a strict financial separation between regulated telephone business and new ventures. Justice Greene set a March 23, 1984 deadline for all RHCs to submit specific requests for waivers or further explanation of the original consent decree.

In April 1984 Bell Atlantic went to court over the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) delay in charging tariffs for customers accessing the local network. Delaying implementation of the access fee not only violated the consent decree, Bell Atlantic charged, but it also caused Bell Atlantic and its sibling RHCs to cover some of AT&T’s service costs in the interim. To make matters worse, because Bell Atlantic was the lowest-cost provider of all the RHCs, it was losing the most money. (The FCC system was one of allocation, with access-fee funds collected first, then distributed to RHCs based on the company’s cost.) Bell Atlantic planned to succeed in spite of the access fee tangle and subsequently allotted more than half of its construction budget for improvement of the network. Bell Atlantic became the first RHC to employ the use of digital termination systems, a microwave technology for local electronic message distribution. The company experimented with a local area data transport system, and planned to install 50,000 miles of optical fiber within a year.

Carving a Niche: Late 1984

Bell Atlantic made several major acquisitions in its first year of operation. The purchase of Telecommunications Specialists, Inc. (TSI), a Houston-based interconnect firm with offices in Dallas, San Antonio, and Austin, was completed in October 1984, and Bell Atlantic planned to let TSI retain its marketing and sales staff and continue operations. TSI, a marketer of private branch exchange (PBX) and key systems, also offered financing for equipment-leasing customers.

In December 1984 Bell Atlantic bought New Jersey’s Tri-Continental Leasing Corporation (Tri-Con), a computer and telecommunications equipment provider. As Tri-Con supplied TSI with financing, Bell Atlantic seemed to be vertically integrating its acquisitions. Another big Tri-Con customer was Basic Four Information Systems, owned by Management Assistance Inc. (MAI). Early in 1985 Bell Atlantic completed the purchase of MAI’s Sorbus Inc. division, the second-largest U.S. computer service firm, with 187 locations and 2,200 employees, for $180 million. Bell Atlantic also bought a related company, MAI Canada Ltd. With the Sorbus acquisition Bell Atlantic hoped to strengthen its position with the federal government; as the company’s largest customer, the federal government provided three percent of total company revenues in the first year of operation.

With the most aggressive diversification of all the RHCs, Bell Atlantic planned to be a full-service company in the increasingly related merging telecommunications and computer sectors. As a struggle for large customers was inevitable, and because the larger customers could potentially set up their own information systems, the company decided to target medium-sized customers. Bell Atlantic offered this customer base everything from information services equipment and data processing to computer maintenance.

Because the original consent decree was drawn to strictly regulate RHC activity and allow long-distance carriers equal access to local networks, fledglings such as Bell Atlantic faced competition on all levels. On the national level, the FCC approved a $2 end-user fee for all subscribers to basic telephone service, another tactic to give the RHCs a cushion in large-business markets. The institution of this fee coincided with the availability of rapidly evolving technology; thus the fee merely encouraged larger customers to create their own information networks, a process termed “bypass.” To help keep Bell Atlantic competitive in the large-customer markets–those most vulnerable to bypass–several states in its region granted the company considerable flexibility in pricing.

Baby Bell Legal Skirmishes in 1985

Of all the unregulated businesses Bell Atlantic was just entering, competition threatened to be even stiffer in the private branch exchange (PBX) market. By early 1985 IBM and Digital Equipment were offering maintenance for their mainframe users, a large portion of Bell Atlantic’s recently acquired Sorbus customer base. Larger than many competing companies nonetheless, Bell Atlantic took advantage of the buyer’s market that the tough competition created; in June 1985 it acquired CompuShop Inc., a retail computer company with $75 million in sales annually, for $21 million. With the acquisition, Bell Atlantic joined siblings NYNEX (the New England and New York RHC), and Pacific Telesis (the West Coast RHC), as surprise competitors in a market that, in spite of a recent surge in sales, was in decline. The retail computer slump was marked by smaller companies’ rapid entry into, and exit from, a market with high overhead costs. The entrance of big names such as Bell Atlantic, retail computer experts argued, could provide just the shot in the arm the market needed to take off.

A year-and-a-half after divestiture, Bell Atlantic, along with its sibling RHCs and other companies, realized that convergence of telephone hardware and computer data processing was a huge business. Over the next several years the RHCs repeatedly petitioned the Department of Justice for business waivers to become more competitive in not only the national but international telecommunications market. Back in July 1984 Bell Atlantic had requested the government waive a body of rules prohibiting the RHCs from supplying their own telephone hardware. Unable to provide equipment for its own Centrex system, Bell Atlantic stood to lose a huge federal government contract to competitors–nearly 370,000 Centrex lines coming up for bid. Having already lost 48,000 Centrex lines due to restrictions of the past year, Bell Atlantic officials thought it was time to confront the issue.

Since divestiture, the FCC allowed AT&T to resell basic services, and it considering letting the company provide customer premises equipment as well. IBM, strengthened by its recently acquired Rolm Corporation and Satellite Business Systems, was not restricted in its marketing efforts, but Bell Atlantic was. By the end of 1985 Bell Atlantic earnings were $1.1 billion on revenues of $9.1 billion. Rated against its competitors, Bell Atlantic was the only RHC close to turning a profit on its unregulated businesses, worth $600 million in revenues. While profits remained strong in Bell Atlantic’s local phone service, its Yellow Pages directory publishing division, due to a disagreement, would be competing with Reuben H. Donnelly Corporation, its previous publisher.

In the meantime, the long-distance market moved uncomfortably close to the RHCs’ local turf. AT&T and other carriers began competing to carry toll calls in local areas. While this would seem to benefit the residential consumer, it did not; outside competitors cutting into RHC profits merely threatened the very profit margin that helped subsidize the cost of local service. Ending its second year in operation, Bell Atlantic’s chairman and CEO, Thomas Bolger, described the restrictions on RHCs as “the most significant problem in the telecommunications industry” in Telephone Engineer & Management’s mid-December 1985 issue and requested the Justice Department come to a decision before the scheduled January 1, 1987 date. If the purpose of the breakup was to promote maximum competition in the industry, the RHCs reasoned that they, the most likely competitors of industry leaders AT&T and IBM, shouldn’t be prohibited from fully competing.

Diversification & More Legal Battles: 1986-88

Continuing to expand its unregulated businesses in spite of, or perhaps because of, line-of-business restrictions as outlined in the consent decree, in September 1986 Bell Atlantic acquired the real estate assets of Pitcairn Properties, Inc. In October the company followed with the $140-million purchase of Greyhound Capital Corporation, since renamed Bell Atlantic Systems Leasing International, Inc. Bell Atlantic then had a firm position in the financial and real estate markets. One month later, Bell Atlantic became the first RHC to propose a new cost allocation plan under recently outlined requirements to the FCC. The corporation also opted, if allowed, to begin planning its comparably efficient interconnection (CEI) system. By March 1987 Bell Atlantic filed its CEI plan asking for the provision of message storage, hoping to get a jump on offering enhanced services. Due to several regulatory restrictions, development of the service was halted. Continuing to acquire attractive companies, Bell Atlantic acquired Pacific Computer Corp., in June 1987 and Jolynne Service Corp. several months later.

In July 1987 Bell Atlantic announced a restructuring plan, combining operations of basic telephone service and unregulated businesses under one newly-created position, chief operating officer (COO). The plan also called for all staff of separate Bell Atlantic telephone companies to report to their respective presidents. Raymond Smith, a Bell employee since 1959, was named COO, reporting directly to Bolger. In September of that year, Judge Greene ruled to uphold the manufacturing and long-distance restrictions on RHCs, while allowing only limited information services. The RHCs all objected, but none as strongly as Bell Atlantic. The corporation alleged that the judge alluded to information discussed during the original consent decree settlement, which claimed that the Bell operating companies, pre-divestiture, had been accused of engaging in anticompetitive practices–remarks not relevant to the case at hand.

The tables turned rather quickly for Bell Atlantic. In January 1988 the company found itself, along with BellSouth, accused of misconduct in bidding attempts to win government contracts. Senator John Glenn of Ohio led the accusations that the two RHCs had been given confidential price information by a General Services Administration chief. Bell Atlantic disputed the charges entirely, claiming that the senator’s report was inaccurate. Despite the legal battles, business transpired as usual with Bell Atlantic selling MAI Canada Ltd., and some of the assets of Sorbus Inc., for $146 million. Following that divestiture, the company purchased the European computer maintenance operations of Bell Canada Enterprises, Inc. Next Bell Atlantic’s Sorbus subsidiary acquired Computer Maintenance Co., Inc., and in 1988, following Judge Greene’s approval of its CEI plans, Bell Atlantic announced the introduction of four new information services: an electronic message storage system (allowing subscribers to record messages for consumers to play back); a telephone answering service; a voice mail service; and a videotex gateway service, through which data bases and customers communicated. All services involved monthly surcharges for customers, as well as an hourly fee for videotex and a one-time user’s fee for message storage.

Juggling its assets a bit more, Bell Atlantic completed the sale of its retail computer CompuShop in June and acquired the assets of CPX Inc., a company specializing in Control Data Corporation equipment in July. Bell Atlantic also acquired the assets of Dyn Service Network.

A New Era in the Late 1980s

Bolger announced his retirement as CEO, effective in January 1989, and COO Smith became the new chief executive officer. Bolger, formerly a vice-president of AT&T in business services and marketing, had led Bell Atlantic through divestiture into a leading position in telecommunications, real estate and leasing finance, and computer maintenance. A strong critic of consent decree restrictions on RHCs, Smith and Bell Atlantic were also active in helping establish international standards for telecommunications. On the national level, however, Judge Greene kept his eye on RHC activities. A Bell Atlantic proposal to conduct a trial involving interstate phone traffic was rejected because it was not deemed a necessity, but rather an advanced, competitive service. Bell Atlantic wanted to cut costs by using a central processor for state-to-state traffic rather than having separate facilities perform the same tasks, and thus held that the judge’s decision was against the public interest.

Bell Atlantic implemented another reorganization in 1989, trimming its management staff by 1,700 through voluntary retirement and other incentive plans. Significant parts of the restructuring included closing the Washington, D.C., Chesapeake, and Potomac Telephone Company headquarters and merging employees into other locations; refinancing various debts; reassessing computer holdings; and outlining a plan to cover future retirees.

During this time, Bell Atlantic invested $2.3 billion in network services to upgrade telephone facilities. Signaling System 7 (SS7), a high-speed information exchange system, was operating on more than 60 percent of Bell Atlantic’s telephone lines. To compete in mobile communications, the company marketed an extremely lightweight cellular telephone; at the same time, Bell Atlantic Paging’s customer base grew, with a 16 percent increase. In partnership with GTE, Bell Atlantic Yellow Pages increased its customer base through a new subsidiary, the Chesapeake Directory Sales Company. Bell Atlantic Systems Integration was formed in 1989 to research and explore marketing capabilities in voice and data communications, as well as in artificial intelligence.

Perhaps the biggest opportunity for Bell Atlantic came at year-end 1989, when it stepped up activity in the international arena. Economic changes in the Soviet Union and eastern Europe opened up entirely new possibilities in global telecommunications. Slowly exploring opportunities abroad since divestiture, Bell Atlantic was, by 1989, assisting in the installation of telephone software systems for the Dutch national telephone company, PTT Telecom, B.V., as well as for the national telephone company in Spain. A Bell Atlantic German subsidiary was awarded a contract to install microcomputers and related equipment at U.S. Army locations in Germany, Belgium, and the United Kingdom. With consultants located in Austria, France, Italy, and Switzerland, Bell Atlantic planned a European headquarters, Bell Atlantic Europe, S.A., to be located in Brussels, Belgium.

Bell Atlantic kept running into challenges stateside, however. In April 1990 the company’s Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company was charged with fraud and barred from seeking federal contracts. Bell Atlantic fought back, citing a double standard in that the U.S. Department of Treasury allowed AT&T to win contracts without necessarily having all the required equipment immediately available, while it had barred the Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company from doing so. Undaunted by its squabbles with the government, Bell Atlantic had created the world’s largest independent computer maintenance organization by 1990, able to service some 500 brands of computers. With the January 1990 purchase of Control Data Corporation’s third-party maintenance business, Bell Atlantic sealed its position as the leader in maintenance of both IBM and Digital Equipment Corporation systems.

Other Bell Atlantic acquisitions of 1990 included Northern Telecom’s regional PBX operations and Simborg Systems Corporation. Through the latter purchase, renamed Bell Atlantic Healthcare Systems, the company provided software for hospital computer networks. Aggressive as ever, in June 1990 Bell Atlantic, along with sibling U S West became the first two Baby Bells to upgrade systems with synchronous optical fiber through the use of Sonet-based equipment. In addition, Bell Atlantic poured over $2 billion into a host of upgrades, including SS7 and ISDN capabilities. In sum, Bell Atlantic offered more choices by year-end 1990 than any information transmission competitor, and its revenues had reached $12.3 billion with earnings of $1.3 billion.

In the early and mid-1990s Bell Atlantic’s international division thrived. In 1990 alone the corporation made several significant ventures, which included teaming up with the Korean Telecommunications Authority in a variety of research, marketing, and information exchanges; joining U S West to modernize Czechoslovak telecommunications; and partnering with Ameritech and two New Zealand companies to acquire the Telecom Corporation of New Zealand. For its $105 million investment in the Czech deal, Bell Atlantic gained 24.5 percent of both the cellular and public data network; in the New Zealand venture, where the network was already digitally-advanced and in a relaxed regulatory environment, the RHCs’ initial investment of $1.2 billion was considered a boon to all involved. Additionally, Bell Atlantic and NORVANS, a Norwegian telecommunications company, jointly applied for a license to develop and operate an independent cellular network in Norway and next came an agreement with the Republic of China to consult in marketing, research, and information exchanges.

Distinguishing Itself: 1991-96

Continuing international expansion, Bell Atlantic joined Belle Meade International Telephone, Inc. in early 1991 to set up a communication system in the Soviet Union; other big news was Telecom Corp. in New Zealand’s successful initial public offering on the New York Stock Exchange in July, and its subsequent announcement to have ISDN capabilities for 90 percent of its customers within three years. Stateside, Bell Atlantic was also on the lookout for complementary businesses and merged its own Bell Atlantic Knowledge Systems, Inc. with Technology Concepts Inc. to form Bell Atlantic Software Systems Inc. Metro Mobile, the second largest independent cellular radio telecommunications provider in the United States, was acquired in 1992. This particular transaction gave Bell Atlantic the most extensive cellular phone coverage on the East Coast, while a joint venture with NYNEX and GTE to combine their respective cellular networks into one huge national service made news from coast to coast.

In 1993 Bell Atlantic bought 23 percent of Mexico’s second largest telecommunications company, Grupo Iusacell, and set to work on a number of projects. On the legal front, Bell Atlantic finally won one, when the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld its right to provide video programming and other services over its established telephone lines. The ruling was a significant win in the cable programming business, as Bell Atlantic was now free to develop video-on-demand, home shopping, and educational programs over telephone wires. The next year, Bell Atlantic and NYNEX moved forward in this area by investing $100 million in CAI Wireless Systems to help in their quest for video programming innovations. Yet before this deal went through, Bell Atlantic made headlines on the legal front again, joining with three other Baby Bells to break the consent decree that had kept them from competing in the long-distance services market.

1995 proved pivotal for Bell Atlantic’s future. A long-awaited ruling in the federal courts gave the company a sweet victory; a federal judge finally ruled in favor of the Baby Bells to offer long-distance services. Bell Atlantic wasted little time, becoming the first Baby Bell to jump into the long distance market by recruiting customers in Florida, Illinois, North and South Carolina, and Texas in early 1996. Bell Atlantic had also been busy overseas as well. The company and Italian conglomerate Ing. C. Olivetti & Co. formed a joint venture in preparation for the breakup of Italy’s telecommunications monopoly three years hence. Telecom Italia SpA, the state-owned company, was due for regulation in 1998, and Bell Atlantic, as well as several other joint ventures, including one from France Telecom, Duetsche Telekom AG, and Sprint Corp., were ready to offer Italians a myriad of choices. Another global venture, Iusatel S.A., Bell Atlantic’s partnership in Mexico with Grupo Iusacell S.A., was given the green light to provide both national and international long-distance services to at least three dozen Mexican cities by the year 2000.

Another major development in 1996 was the announcement that Bell Atlantic and NYNEX would merge and become the nation’s second largest telephone company. Though the official announcement came as a surprise to few (rumors had been swirling for months), the deal was at once controversial and ironic–once-struggling Baby Bells were beginning to rival their old parent company. Soon after news of the merger was made public, a new operating unit called Bell Atlantic Internet Solutions debuted, giving customers in Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and New Jersey a wide range of both business and residential Internet-based products and services.

The New Bell Atlantic: 1997 and Beyond

Bell Atlantic’s merger with NYNEX was completed in early 1997. The new company’s assets serviced 25 percent of the overall U.S. market in 13 states and accounted for about 140-billion minutes of long distance traffic; the region not only held one-third of the Fortune 500’s headquarters, but the U.S. government’s nerve center as well. South of the border, Bell Atlantic continued its varied international coups, this time investing another $50 million in its Mexican venture to gain controlling interest in Grupo Iusacell, of which it had previously owned 42 percent.

By early 1998, the new Bell Atlantic had 39.7 million domestic access lines, 5.4 million domestic wireless customers, 6.3 million global wireless customers, and services in 21 countries worldwide. The company was also the world’s largest publisher of both print and electronic directories, with over 80 million distributed annually. After a rocky road as Bell Atlantic’s local markets were forced open to competitors, the company was taking advantage of new opportunities in the $20 billion long-distance market and the $8 billion video market, and was continuing to expand globally.

In June of 2000 Bell Atlantic acquired GRE in one of the largest mergers in the history of the United States. The merger was a lengthy process and took nearly two years to finalize and for approvals to be received from the shareholders of both companies as well as the FCC and state regulatory commissions of 27 states. On April 4th of 2000 the merger was complete and the company would now be known as Verizon Wireless. The new company name was derived from the Latin word veritas which means truth and the word horizon which signified that the company would be full of limitless potential.

In June of 2000 GTE wireless joined the merger which made Verizon the largest wireless provider within the United States. This title held strong for a few years until AT&T and Cingular joined forces. In 2002 the former telephone operations of GTE were sold in three different states. These sales led to the creation of CenturyTel in Missouri and Alabama which eventually purchased Embarq and changed their name to Century Link. In 2006 Verizon sold their Verizon Dominicana stakes in Puerto Rico to America Movil and Telmax for almost $4 million.

In 2007 the company sold their New England operations in Vermont, Maine and New Hampshire which were then merged with Fair Point Communications. This deal originated in 2007 yet did not finalize until April 1st of 2008. One of the biggest sell offs of Verizon took place when the company sold all of their wire line assets to Frontline Communications. This deal finalized on July 1st of 2010. Another important acquisition which occurred in 2010 was that of Alltel which made Verizon the largest wireless provider within the United States.

The 4G LTE was launched in December of 2010 which took advantage of the innovative 4G technology which is currently the fastest available in the United States to date, providing data speeds as much as ten times faster than 3G. One of the biggest announcements for the company in 2011 was the announcement that Verizon would soon be offering the once AT&T dominated iPhone to its customers starting in February 2010.