On December 11, 1986, Unisys registered the unisys.com domain name, making it 49th .com domain ever to be registered.

Unisys Corporation is an American global information technology company based in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania, that provides a portfolio of IT services, software, and technology. Unisys Corporation is a major provider of computer-related services and technologies to customers in the financial services, communications, transportation, publishing, commercial, and government sectors, in more than 100 countries. The company offers an integrated suite of products and services known as Unisys e-@ction Solutions designed to help its customers meet the challenges and seize upon the opportunities of the Internet economy. Unisys provides consulting, systems integration, and outsourcing services; designs, implements, and maintains computer networks and multivendor information systems; and manufactures high-end, mission-critical servers for such organizations as the NASDAQ and the New York Clearinghouse.

Company History:

Unisys traces its roots back to the founding of American Arithmometer Company (later Burroughs Corporation) in 1886 and the Sperry Gyroscope Company in 1910. Unisys predecessor companies also include the Eckert–Mauchly Computer Corporation, which developed the world’s first commercial digital computers, the BINAC and the UNIVAC.

In September 1986 Unisys was formed through the merger of the mainframe corporations Sperry and Burroughs, with Burroughs buying Sperry for $4.8 billion. The name was chosen from over 31,000 submissions in an internal competition when Chuck Ayoub submitted the word “Unisys” which was composed of parts of the words united, information and systems. The merger was the largest in the computer industry at the time and made Unisys the second largest computer company with annual revenue of $10.5 billion.

Adding Machine Origins

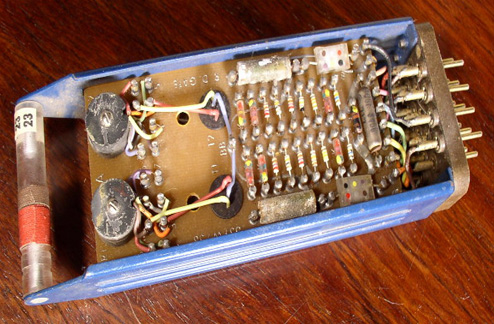

Unisys, formed from the 1986 merger of the Burroughs Corporation with Sperry Corporation, traces its origins to over 100 years before that; in 1885, William Seward Burroughs invented the first recording adding machine. Burroughs called his device an arithmometer and the next year he and three partners founded the American Arithmometer Company in St. Louis, Missouri. Creating a commercially viable version proved difficult; Burroughs was unable to patent a salable model until 1892. Once on the market though, the adding machine became a success–in 1897 Burroughs was awarded the Franklin Institute’s John Scott Medal in honor of his invention. Burroughs died of tuberculosis the next year, however, sadly before realizing much profit from his invention. The company, which moved to Detroit in 1905, was renamed the Burroughs Adding Machine Company in his memory.

During the early years of the 20th century, Burroughs consolidated a position in the adding machine business by acquiring both Universal Adding Machine and Pike Adding Machine in 1908, and Moon-Hopkins Billing Machine in 1921. By 1914 the company offered 90 different types of data-processing machines which, with the help of interchangeable parts, could be modified into 600 different configurations. Accountants formed the core customer base, and in 1917 Burroughs increased courtship of those customers with the debut of a magazine devoted to accounting called Burroughs Clearing House. By the 1920s Burroughs was an established mainstay of the office-machine industry and remained so for the next three decades, with adding machines still at the heart of the product line.

1950s: Expanding into Computers

All of that changed, however, as a result of J. Presper Eckert and John W. Mauchly’s invention of ENIAC, the first electronic computer, in 1946. At first the market for computers appeared to be limited to a handful of government agencies that used them for large-scale number crunching. The only companies to commit themselves to computer research and development were large electronics and office-machine firms for whom the computer was a natural extension. When the Defense Department awarded the design contract for the new SAGE early-warning computer system in 1952, Burroughs, IBM, RCA, Remington Rand, and Sylvania were all prime choices. IBM won, giving that company an advantage competitors struggled to overcome.

Burroughs did not immediately plunge wholeheartedly into computer technology, preferring, along with Sperry Rand’s UNIVAC unit, NCR, Control Data, and Honeywell, to keep up with IBM during the 1950s. At the end of the decade Burroughs’s reputation was still, in the words of a Time magazine correspondent, that of ‘a stodgy old-line adding machine maker.’ Even so, in 1952 the company developed an add-on memory for Eckert and Mauchly’s ENIAC. The following year the company name was shortened to Burroughs Corporation, in recognition of its diversification. In 1956 Burroughs introduced its first commercial electronic computer and acquired ElectroData Corporation, a leading maker of high-speed computers. Burroughs also entered the field of automated office machines, introducing the Sensitronic electronic bank bookkeeping machine in 1958.

Burroughs entered the computer field during the tenure of John Coleman, whose last major act as president was to negotiate a partnership agreement between his company’s computer operations and those of RCA, which was also looking for a way to catch up to IBM through a pooling of financial resources. RCA approved the agreement in 1959, but Coleman died before he could sway Burroughs’s board of directors and the plan was never realized. Business historian Robert Sobel wrote that the Burroughs-RCA partnership might have produced ‘the best possible challenger for IBM.’

1960s Through Early 1980s: Struggling to Compete with IBM

Coleman was succeeded by executive vice-president Ray Eppert. Under Eppert, Burroughs expanded its place in the rapidly growing bank-automation market in 1960, as the company began selling magnetic inks and automatic check-sorting equipment. In 1961 the company introduced the B5000 computer, which was less expensive and simpler to operate than other commercial mainframes. Expansion and diversification during the early years of the computer age led to a fourfold increase in sales between 1948 and 1960, from $94 million to $389 million. At the same time, however, increased research and development costs cut profit margins, a problem the company struggled with until the late 1960s.

Despite this surge in earnings, Burroughs remained among the smallest of IBM’s main competitors in the early 1960s. Although the B5000’s distinctive design had earned a solid following, Burroughs’s computer product line remained narrow and the company was still too dependent on accounting machines. Research and development costs continued hacking away at profit margins, leaving the company’s future clouded.

In 1964 Ray Macdonald became executive vice-president and began overseeing the company’s day-to-day operations. With the help of several like-minded executives, he took control of Burroughs from Eppert and committed the company to a course of steady profit growth through cost cutting. Macdonald succeeded Eppert as CEO in 1967. Burroughs’s financial performance continued improving and the company became a Wall Street favorite before the decade was out.

The Defense Department awarded Burroughs a contract in 1967 to build the Illiac IV supercomputer which had been designed by a team at the University of Illinois–a major coup for the company. The Illiac IV was ten to 20 times faster than any existing supercomputer in 1972 and was delivered to NASA’s Ames Research Center in California. The sudden lag in research and development created by Macdonald’s policy of cutting costs also contributed to two significant technical failures around this time. The B8500 mainframe, which had been scheduled for delivery in 1967, had to be scrapped altogether in 1968, after Burroughs engineers realized they could not produce reliable components at a reasonable price. The B6500 was riddled with breakdowns caused by the development team’s strategy for bringing the project in on time and under budget–namely, cutting corners in the high-speed circuitry design and neglecting to test the completed machines properly before delivery.

An interesting aspect of Macdonald’s stewardship was his reemphasis on accounting machines as an integral part of Burroughs’s product line. Foremost among his talents was a genius for salesmanship; the company won a considerable chunk of the high-speed accounting machines market from rival NCR. In 1974 Burroughs entered the facsimile equipment business, acquiring Graphic Services for $30 million. The next year the company paid $8.8 million for Redactron, a maker of automatic typewriters and computer-related equipment.

Ray Macdonald retired in 1977 and was replaced by Paul Mirabito, his hand-picked successor. During Mirabito’s brief tenure, the consequences of Macdonald’s fiscal policies began manifesting themselves in earnest. In 1979 IBM announced a powerful new generation of computer systems. Burroughs countered by announcing its own new series of systems. Unfortunately, although Burroughs’s design ideas were good, the company did not have the development or manufacturing resources to translate them into actual computers. Burroughs’s inability to deliver finished products resulted in an embarrassing stream of canceled orders. Years of salary cuts and other forms of budget-tightening had engendered low morale among field engineers and a reputation for poor service among clients. Customer complaints came to a head in 1981, when 129 Burroughs users sued the company over product unreliability and difficulty in getting their machines fixed.

Mirabito had retired in 1979 and was replaced by W. Michael Blumenthal, the former chairman of Bendix and secretary of treasury in the Carter administration–a move that surprised many industry observers. Blumenthal took over a company that was deceptively profitable, chalking up record sales of $2.8 billion in 1979. He immediately set about shaking up Burroughs’s corporate culture, firing veteran executives and replacing them with his own appointees, phasing out the adding machine and calculator businesses, implementing a plan to improve repair service, and discontinuing accounting practices that tended to inflate earnings. Blumenthal’s reforms did not come without cost, however; in July 1980, the company reported its first drop in quarterly profits in 17 years.

Blumenthal concentrated on Burroughs’s computer business in an effort to secure the position of the largest of IBM’s U.S. competitors. In 1981 the company covered one weak spot by acquiring System Development Corporation, a software development firm, for $9.6 million. Burroughs also procured Memorex that year, maker of disc drives and other data-storage equipment, for $85.2 million, despite Memorex’s shaky financial condition. These moves added $1 billion to the company’s annual sales.

Mid-1980s: Burroughs + Sperry = Unisys

Blumenthal eventually decided that economies of scale were necessary to compete with IBM. In 1985 Burroughs launched a $65-per-share takeover bid, worth $3.7 billion, for Sperry Corporation. Sperry had been a takeover candidate since holding unsuccessful merger talks with ITT in March 1984. The Sperry board of directors and investors, from whom Burroughs hoped to obtain shares, balked at the offer, though, and the deal fell through. Burroughs came back with a $70-per-share bid, worth $4.1 billion, in May 1986, and a four-week battle ensued. Sperry executives, anxious to preserve the company’s independence, argued against selling out. The board put up a defense that included an $80-per-share stock buyback offer while casting about for a white knight. Sperry eventually agreed to a $76.50-per-share deal worth $4.8 billion–at the time, by far the largest merger in the history of the computer industry and one of the largest in U.S. corporate history. The resulting company was the second largest computer firm in the nation, leapfrogging over Digital Equipment Corporation.

Sperry, which was founded in 1933 but traced its roots back to the 1910-formed Sperry Gyroscope Co., originally made aircraft instruments. In 1955 the manufacturer jumped into the computer business, merging with Remington Rand, whose history dated back farther than Burroughs or Sperry. In 1873 E. Remington & Sons, forerunner of Remington Typewriter Co., introduced the first commercially successful typewriter. After producing the first ‘noiseless’ typewriter in 1909, Remington introduced the first electric typewriter in the United States in 1925. Two years later, Remington Typewriter merged with Rand Kardex to form Remington Rand. The latter introduced the world’s first business computer, the 409, in 1949. The following year, Remington Rand acquired Eckert-Mauchly Corporation, the company founded by the developers of the ENIAC and the UNIVAC. The 1955 merger of Sperry and Remington Rand resulted in Sperry Rand, which quickly became one of the industry’s leading companies due to its technical prowess and by the 1960s had gained a reputation for wonderful products. At the same time Sperry had inherited a legacy of poor management and marketing from Remington Rand. By the time Burroughs showed interest, the renamed Sperry Corporation had profitable defense-electronics operations, but a struggling computer business.

Six months after the acquisition, the combined company adopted the name Unisys Corporation. The moniker was selected from suggestions submitted by Burroughs and Sperry employees and was conceived as a synthesis of the words ‘United Information Systems.’ But the real work of fusing the two companies still remained. Over the next two years the Unisys workforce was reduced by 20 percent–24,000 of the 121,000 positions were eliminated–while unwanted and redundant businesses were placed on the market in order to generate cash. In December 1986, Unisys sold Sperry Aerospace to Honeywell and later sold off Memorex’s marketing arm.

Late 1980s and Early 1990s: Sinking Fortunes and a Turnaround

Meanwhile Unisys stepped up diversification of its product line. In 1987 Unisys obtained Timeplex, a high-tech communications equipment company, for $300 million, and Convergent Technologies, a maker of office workstations, for $351 million. By 1989 the company had begun to move into the small and mid-sized computer market, adopting AT & T’s popular Unix operating system as the standard configuration for Unisys machines. In 1989 Unisys also began manufacturing its own personal computers for the first time.

Unisys was not entirely successful in the late 1980s, however. Despite strong earnings growth from the time of the Sperry deal through 1988, the company posted a loss of nearly $100 million in the first quarter of 1989. Management shakeups in 1987 had resulted in the departure of two key executives–vice-chairman Joseph Kroger, the former president of Sperry who commanded intense loyalty from former Sperry employees, and Paul G. Stern, a physicist whom Blumenthal had brought into the company from IBM and made president and chief operating officer in 1982. Sluggish sales, manufacturing cost overruns, and fierce price competition among the many companies using the Unix system all cut into revenues.

Unisys also found itself caught up in the Pentagon procurement scandal of 1988. Federal prosecutors brought charges against some Unisys executives–including former vice-president Charles Gaines, who headed the Washington, D.C., office of one of the company’s defense units–with fraud, bribing Defense Department officials into yielding classified procurement documents, and making illegal campaign contributions to members of Congress; these activities allegedly occurred at Sperry prior to the merger. Unisys had already begun an internal investigation when the government made the accusations public. According to Paul Mann of Aviation Week & Space Technology, the company settled its part in the Operation Ill Wind court case in September 1991, pleading guilty to fraud and bribery and agreeing to pay a record of up to $190 million in damages, penalties, and fines. In the same article, James A. Unruh, who succeeded Blumenthal in 1990, was quoted as saying, ‘we as a company must accept responsibility for the past actions of a few people, even though today we have a completely different management team and different shareholders.’

Unisys’s difficulties continued and deepened in the early 1990s, with much of the troubles easily traced back to the merger of Burroughs and Sperry. The operations of the two companies had never been properly integrated, leaving duplicate R & D, marketing, and accounting departments. Already saddled with a huge debt load from the 1986 merger, Unisys was forced to take on an additional $1.4 billion in debt to cover negative cash flow, as the company’s mainframe computers were quickly losing market share to IBM and Amdahl. The company’s stock, which sold for about $50 in 1987, collapsed to a low of $1.75 during 1990. Unisys posted successive net losses of $639 million in 1989, $436 million in 1990, and $1.39 billion in 1991. Bankruptcy neared.

Amid a depressed global economy, Unruh managed to turn Unisys’s fortunes around by 1992 through a draconian restructuring, the success of which surprised many observers. Unisys exacted additional drastic employee reductions, eliminating some 23,000 people from 1989 through 1991. At the end of 1991, the remaining Unisys workforce was roughly half the size of that at the time of the merger. An additional 6,000 jobs were cut in 1992, leaving a workforce of 54,300. Other major restructuring costs led Unisys to take massive charges of $1.2 billion in 1991, directly contributing to overall unprofitability for the year. These measures, however, were expected to reduce costs on an annual basis by approximately $800 million. In its aggressive drive to cut costs, Unisys reduced its 50,000-product line by 15,000 items, having determined that ten percent of its products were bringing in 90 percent of the revenue. Its mainframe computer lines were reduced from four to two (Sperry’s 2200 series and Burroughs’s A series). The Timeplex subsidiary, responsible for only a small fraction of overall revenues, was divested. The company shuttered seven of its 15 manufacturing facilities, and Unisys began concentrating on those market sectors where it was traditionally the strongest: banking, airlines, government, and communications. Debt was brought down to a more manageable $1.4 billion, from its peak of $3.5 billion.

This massive reengineering effort not only pulled Unisys from the brink of disaster, it also resulted in two solid years of financial performance: for 1992, net income of $361.2 million on sales of $8.7 billion, and for the following year, net income of $565.4 million on $7.74 billion in revenues. Unisys was much smaller–revenues had totaled $10.11 billion in 1990–but much more profitable.

Mid-1990s and Beyond: Shift to Services and Continued Restructuring

As the turnaround was taking shape, Unruh pushed the company in a new direction. With a clear shift taking place from mainframes to networked computing, Unruh moved to deemphasize the former through an expansion into computer services. Beginning in 1992 with the formation of a unit dedicated to providing information technology services, Unisys became active in the areas of systems consulting and design and systems integration services. One rationale behind the shift to services was that as computer systems grew ever more complex, in-house personnel were less and less able to cope, leading to a growing market for outside information technology expertise. Building on its existing mainframe maintenance activities, Unisys was able to generate $1.3 billion from services in 1992, then $2 billion the following year. By 1994 the company’s ‘services and solutions’ unit was generating more revenue than the mainstay mainframe hardware operations.

Unfortunately, Unisys’s comeback proved short-lived. Services revenues were growing about 30 percent per year but the company had failed to make a profit from its new activities, losing about $54 million during 1995 alone. Part of a 1994 profit decline was attributed to a delay in getting the company’s latest servers, the 550 and 580, to market. Another factor was a $186 million charge for a further restructuring of the mainframe operations, including a workforce reduction of 4,000 and the long overdue merging of the 2200 series and the A series into a single mainframe line. After the depressed profit figure of $100.5 million for 1994, Unisys posted a net loss of $624.6 million in 1995 thanks to a $717.6 million charge for another restructuring (the fifth in seven years). This time the company reorganized itself into three units: hardware and software, which included mainframes, servers, and a recent foray into PCs; maintenance and networking, which concentrated on servicing and connecting computers; and services, which involved consulting and outsourcing in integrated systems design. This restructuring also involved the paring of a few thousand more workers from the payroll and the consolidating of facilities and manufacturing, as well as the 1995 sale of its defense contracting unit to Loral for $862 million.

The following year Unisys introduced to positive market reaction the ClearPath line of computers, which combined proprietary mainframes with open systems capable of running standard Unix and Windows NT software and applications in a single system. In April 1996 Unruh managed to defeat Greenway Partners’ proposal to shareholders for a breakup of Unisys into three parts. (Greenway held nearly a five percent stake in Unisys.) A similar breakup proposal one year later failed as well. In September 1997 Unruh stepped aside from his leadership position at Unisys, having kept the company alive but having never fully turned it around. The financial ups and downs and the frequent restructurings had left the remaining workforce demoralized. Nevertheless, most observers praised Unruh’s shift into services, and during 1997 that unit finally turned its first profit.

Unruh helped select his successor, Lawrence A. Weinbach, former head of accounting and consulting giant Andersen Worldwide. The new chairman, CEO, and president immediately began working to improve employee morale, meeting with more than one-third of the workforce and revoking unpopular policies from recent austerity programs, such as the elimination of the company match on 401(k) contributions. Weinbach also initiated $1.04 billion in fourth-quarter 1997 charges, which resulted in a net loss for the year of $853.6 million. Some $900 million of the charges were to write down the value of goodwill left from the acquisition of Sperry, with the remainder going toward reducing debt. At year-end 1997 debt stood at $1.4 billion but was reduced to less than $1 billion by the end of 1999.

In addition to focusing on debt reduction, Weinbach moved Unisys out of the manufacturing of PCs and smaller servers. The company began outsourcing the manufacture of such hardware to Hewlett-Packard in 1998. He also jettisoned the company’s three unit structure in favor of a simpler division between hardware, which would now focus on high-end servers and mainframes, and services, which included maintenance as well as consulting and systems design. On the hardware side, Unisys worked to upgrade its existing mainframe line, while also introducing in 1999 a mainframe-class server called the Unisys e-@ction ClearPath Enterprise Server, which was Intel microprocessor-based and ran Windows NT (later Windows 2000) software. This server was part of a comprehensive and integrated portfolio of hardware and services–known as Unisys e-@ction Solutions–that Unisys unveiled in 1999 to support the burgeoning e-business market. On the services side, Unisys became more selective in the type of projects it took on, concentrating on key markets where it had the most expertise–including financial services, government, communications, transportation, and publishing.

By 1999, 70 percent of the company’s revenues were being generated by the services operations. For the year, Unisys posted net income of $510.7 million on sales of $7.54 billion, its best year since 1993. It was difficult to predict whether this turnaround would last longer than that of the early 1990s. As Unisys’s services side grew, profit increases were likely to be harder won, as its services business was markedly less profitable than its hardware side. Nevertheless, one possible avenue for early 21st-century growth was in international markets, and Unisys was seeking acquisitions to fuel an overseas push in services. In 1999 the company made several acquisitions, including Datamec, a Brazilian application outsourcing company, and City Lifeline Systems Limited, a U.K.-based provider of services and solutions for firms trading in fixed-income securities.