X.25 protocol approved

Date: 01/01/1976

X.25

X.25 was developed by common carriers in the early 1970s and approved in 1976 by the CCITT, the precursor of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), and was designed as a global standard for a packet-switching network. X.25 was originally designed to connect remote character-based terminals to mainframe hosts. The original X.25 standard operated only at 19.2 Kbps, but this was generally sufficient for character-based communication between mainframes and terminals.

Because X.25 was designed when analog telephone transmission over copper wire was the norm, X.25 packets have a relatively large overhead of error-correction information, resulting in comparatively low overall bandwidth. Newer WAN technologies such as frame relay, Integrated Services Digital Network (ISDN), and T-carrier services are now generally preferred over X.25. However, X.25 networks still have applications in areas such as credit card verification, automatic teller machine transactions, and other dedicated business and financial uses.

How X.25 Works

The X.25 standard corresponds in functionality to the first three layers of the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) reference model for networking. Specifically, X.25 defines the following:

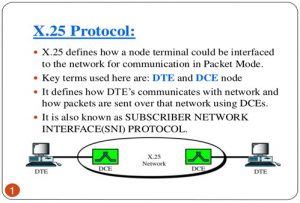

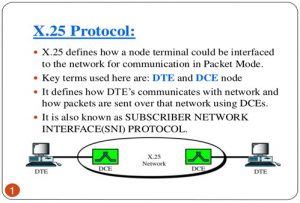

The physical layer interface for connecting data terminal equipment (DTE), such as computers and terminals at the customer premises, with the data communications equipment (DCE), such as X.25 packet switches at the X.25 carrier’s facilities. The physical layer interface of X.25 is called X.21bis and was derived from the RS-232 interface for serial transmission.

The data-link layer protocol called Link Access Procedure, Balanced (LAPB), which defines encapsulation (framing) and error-correction methods. LAPB also enables the DTE or the DCE to initiate or terminate a communication session or initiate data transfer. LAPB is derived from the High-level Data Link Control (HDLC) protocol.

The network layer protocol called the Packet Layer Protocol (PLP), which defines how to address and deliver X.25 packets between end nodes and switches on an X.25 network using permanent virtual circuits (PVCs) or switched virtual circuits (SVCs). This layer is responsible for call setup and termination and for managing transfer of packets.

An X.25 network consists of a backbone of X.25 switches that are called packet switching exchanges (PSEs). These switches provide packet-switching services that connect DCEs at the local facilities of X.25 carriers. DTEs at customer premises connect to DCEs at X.25 carrier facilities by using a device called a packet assembler/disassembler (PAD). You can connect several DTEs to a single DCE by using the multiplexing methods inherent in the X.25 protocol. Similarly, a single X.25 end node can establish several virtual circuits simultaneously with remote nodes.

An end node (DTE) can initiate a communication session with another end node by dialing its X.121 address and establishing a virtual circuit that can be either permanent or switched, depending on the level of service required. Packets are routed through the X.25 backbone network by using the ID number of the virtual circuit established for the particular communication session. This ID number is called the logical channel identifier (LCI) and is a 12-bit address that identifies the virtual circuit. Packets are generally up to 128 bytes in size, although maximum packet sizes range from 64 to 4096 bytes, depending on the system.